A Flood

of Creativity

I have come to the

conclusion that without some kind of struggle,

there will be no great art. Most of the biographies you will read in this rusty, iron

box are not very happy ones. It seems the greater the adversity, the greater

the achievement. As people, countries or cultures nestle into relative ease and

comfort, they flat-line, and great groundbreaking art is the first thing to

disappear.

The book called the Agony and the Ecstasy

is more than the biography of a Renaissance master, it is a blueprint for

creativity. It is significant that even

blacks, in my humble opinion have fallen victim to this pattern. Michael

Jackson’s tragic flaw, which led him and his potential to destruction instead

of lasting glory, was his lack of connectedness to real life and real struggles.

Michael Jackson was the American Wagner. As the Renaissance had its last, most

impressive yet degenerate, self absorbed , over the top era called Baroque, so

has our dynamic era of American music; an awe-inspiring era without soul but

teaming with technical prowess. The struggle is over, the problems solved, the

folks easily bored and the artists left with nothing new under the sun, but the

wow factor driving sales and commissions, dependant on the constant evolution

of new technologies.

But no hunger; no urgency, and no new

ideas. Hollywood is the hollow bastion of this inevitability. It’s anybody’s

guess where the next art will emerge, probably from a third world country, a

culture on the rise… and in the 1940’s and 50’s African Americans were still

such a people and a people to be reckoned with...

In the

Brazos bottom, farmers have always had to build their barns up high off of the

ground in order to protect their harvests and perishables from annual flooding.

After years of struggling against nature, people find solutions to make life

possible, no matter where they are. Like architecture, art is just problem

solving. An interesting creation was born, but the devastating flood had to come first.

Cowboys on the Blakeley

Ranch, around 1917

Sadly for

blues, it was sometimes a flood of blood. Race hate-crimes continued well into

the 1930’s. When they happened, most whites just shrugged their shoulders. Young Texans who idolized John Wesley Hardin

continued to look for victims. An outlaw gang of whites in Harris County

provoked a short but bloody range war near Clodine. Black ranch hands for the

famed Blakeley Ranch, known today as Cinco Ranch, found themselves in a

shooting war with Texas gunmen who still knew no boundaries for their race hate

or blood lust. After losing a family member in an apparent assassination, the

crazed white killers surrounded Blakeley’s ranch hands and set their house on

fire. The inhabitants were picked off with Winchesters, one by one as they fled

the inferno. None survived, and none were prosecuted. But thankfully, these were some of the last

overt murders by psycho sons of the South who terrorized Texas blacks for

several generations.

But no

sooner had this kind of senseless killing started to wane, than bored

Depression youths picked up guns and started anarchic crime sprees throughout

the Midwest. The old Southern patron saints of justifiable genocide had

inspired a whole new generation of wanton killers. John Wesley Hardin and Jesse

James gave clean-cut Bonnie Parker, a Dallas waitress, and Clyde Barrow, a poor

saxophone player, a self-serving cause that propelled them into short-lived

fame and sure annihilation. Themselves big blues fans, they posed for

photographs and wrote self-pitying poetry about crime.

Wanna-be desperados,

Buck and Clyde Barrow pose with Raymond Hamilton.

In a few

years their gang had killed over a dozen people, nine of them police officers.

They were so nasty that John Dillinger complained that they gave bank robbing a

bad name. A big legendary Texas Ranger

led the search for them. Super sleuth Frank Hamer, Mance Lipscomb's old friend, was hand-picked to take them

out. The veteran Ranger had no more sympathy for east Texas gangsters than he

did for haughty Navasota thugs. On special assignment, he tracked them

relentlessly, until one day in 1934 he met them driving down a country road in

Louisiana, and ended their foolishness once and for all. Backed by numerous

well-armed lawmen, he stood in the road with his Remington Semi-automatic, and

held up his hand. The desperate couple went for their guns and immediately felt

the sting of fifty bullets. Bonnie had already written her catchy farewell:

“Some day

they’ll go down together;

They’ll bury

them side by side;

To few it’ll

be grief-

To the law a

relief-

But its

death for Bonnie and Clyde.”

Bonnie

Parker turned out to be a very talented writer and poet, just not a

prophet. She and her lover were not

buried together, in spite of her romantic vision. After all, her mother would

have argued, they were not even married! But there is no doubt she came alive

artistically as she plunged into Clyde’s struggle, and walked his walk. Crime

has always been an unfortunate alternative for creativity.

In sinc with

my theory, art became not only a coping device but an effective offensive

weapon, just as blues singers seemed to multiply with every outrage against

their race. A survey of post war trans-Brazos blues can be a cultural

eye-opener, as this quiet, almost forgotten region raises her wing to expose

her bountiful nest full of hatchlings. The conditions that incubated the post

WWII Trans-Brazos blues scene were not a great deal different from those that

gave rise to their fathers. But the environment was incrementally softer and

kinder, and blues musicians became more courageous and prolific as their craft

gained worldwide acceptance. This would be the class that took the hill and

eclipsed every other musical influence in America.

Not only had

blues gained popularity, and blues musicians enjoyed financial rewards like

never before, but they began to see their old enemies and obstacles begin to break down in front of them. The iron hand of Southern white

supremacy became a caricature of itself. The World began to look at the old

ways of the American South as an anachronism. The policies of

disenfranchisement and Jim Crow laws of Texas were an embarrassment, their

proponents stubbornly taking their ideals to the grave.

The

uncompromising lions of Southern racism grew old, and some of them found no

comfort in their empires, built in the topsoil of oppression and on the backs

of black men under their whips. As if

Faulkner himself had written this script, old Judge J. G. McDonald of Anderson

tossed and turned in his sleep, mumbling about mysterious fights and people who

were out to get him. Tormented by hallucinations, obsessed with days in the

past, he was absolutely convinced that, even in his old age, there was somebody

that wanted him dead. Perhaps there were.

Perhaps he remembered the schemes and dreams

he instigated decades before, that were, even to his own reckoning, crimes

against true American ideals, and all of Humanity. Perhaps for some, Hell is living with the

unconscionable wrongs you have done. Inconsolable, his friends called in

experts, and his family doctor finally committed him to the Austin State

[Mental] Hospital. He was “…unquestionably of unsound mind.” That, for many

black folks in Grimes County, was no news at all. The man who hypnotized the

conscience of a County and turned everything upside down was dying a thousand

deaths, and no longer able to discern truth or stand her consequences. God

showed him mercy in 1938, and allowed his suffering to end, right when

trans-Brazos blues took the International stage.

A bumper crop fills the

streets of Navasota around 1945.

And the

ironies just kept chugging away. The Blues Valley legacy ultimately wove itself

into a Hollywood legend. In 1939 Metro Goldwyn Mayer released Gone With the

Wind, the first major motion picture to objectively face the War Between the

States and the Reconstruction era, and American race relations ever since. The

movie was respectful of Southern pride, but amply illustrated stereotypical

Southern flaws of character. It was an empire that had to be crushed, for

America to ever be what she was designed to be. Sure the film had its flaws,

but nobody who watched it failed to fall in love with sweet, dear little

Melanie Wilkes. She embodied everything good in the South, in a swirl of

worldly vipers. As it turned out, Olivia DeHaviland, who so convincingly played

Melanie, and in fact became the archetype of the Southern damsel, married

Marcus Goodrich in 1946, grandson of Texian B. B. Goodrich. She proudly named

her son Benjamin Briggs Goodrich, taking great pleasure that her son carried

the blood of the line who established the Republic of Texas. But poor guy, his

genes must have attacked one another immediately upon conception.

Mr. and Mrs. Marcus Goodrich

A cross between Hollywood and Western

adventure, Benjamin Goodrich grew up to be…

a mathematician. Without some kind of

struggle, there will be no great art.

Many of the

following musicians shouldered a multitude of struggles, and several proudly

served their Country in WWII, in uniform. This was a much downplayed rite of

passage for many black men, who came home standing a little straighter, their

hearts even fiercer, and minds infinitely wiser. If they did not actually

serve, they still identified with the American soldier, and somewhere in the

struggle, began to root for him. Black men had shown the willingness to enlist

and shed blood for a land that had shown them little acceptance. And as black

men bled red blood that mingled with white men’s, they purchased begrudging

respect, and even affection. In the process they introduced their music to

clubs all over the globe.

Europeans were curious about these agile and hearty warriors, who still wore the legacy of freedman. This identity gave them a prominent platform, and they were able to introduce their message to a broad, and soon to be devoted audience. Blues enthusiasts in Europe are so faithful, as to shame us who live where it was born and know nothing about it.

Europeans were curious about these agile and hearty warriors, who still wore the legacy of freedman. This identity gave them a prominent platform, and they were able to introduce their message to a broad, and soon to be devoted audience. Blues enthusiasts in Europe are so faithful, as to shame us who live where it was born and know nothing about it.

This next generation of blues artists

pioneered the post-war blues and subsequently invented rock & roll. Soon British

“rock” groups picked up their songs and made them marketable to the whole

world. Near the mouth of the mighty

Brazos, Houston, Texas was an active mecca for musicians in the region to come,

learn and record. They came from all over east Texas and brought their blues

adaptations to be refined and marketed. Trans-Brazos blues had roots in the

most rural dives in the country bottoms, but it had also adapted to modern

electric sounds. By now blues artists were migrating to faster, more upbeat

lyrics, often calling their new blues style jazz, or “boogie woogie” or “rhythm and

blues.” They reflected country and gospel and blues traditions, and borrowed

from and loaned freely to each. But B.

B. King and others freely admit, it’s all blues…

Buster Pickens

Buster Pickens

Edwin Goodwin “Buster” Pickens is the forgotten glue that tied much of the Trans-Brazos

Blues musicians together. A greatly sought after “sawmill” pianist, Buster was

born in Montgomery County in 1916 but called Hempstead, Texas home. Buster served his Country during WWII, and

came home after the war to find a fertile blues market. He is known to have

contributed to at least 17 blues albums, and at different times in his life,

Buster was the back-up pianist for Goree Carter, Alger “Texas” Alexander, and Perry

Cain. He was in Lightnin’ Hopkins’ Quartet, but made only one solo album in

1960.

Buster

Pickens is the standard by which most Texas Blues piano is compared. He was

featured in the short movie “The Blues” in 1962. Just when it appeared that he

might finally attain the recognition he deserved, he was murdered during a

dispute over a dollar in a ballroom brawl in Houston. Buster Pickens was only 48 years old.

L. C. “Good Rockin” Robinson was born in Austin County in 1918. He spent a lot of time in Brenham and

Somerville during his youth, and later his sister married Blind Willie Johnson and he picked up some

slide guitar techniques from him. One evening after a gig he met Bonnie and

Clyde, who had a special request, and begged him into a spontaneous if not

awkward street performance, and paid him well for it. He developed his playing

skills while working in the daytime as a cotton farm worker near Temple. And

like his brother-in-law, gospel was a major part of his music, which he carried

to California after WWII, where he thrilled audiences with his versatility.

Robinson and

his brother played all kinds of music, even some country tunes. Bob Wills’

steel guitar player Leon McAuliffe met and impressed L. C. with his lap steel

sound, and L. C. made the conversion to lap-steel guitar, which he played with

dazzling ability. He also played the guitar and the fiddle with electric

virtuosity.

L. C. became

a Blues legend in California, where he recorded with Muddy Waters and other

Blues masters. His older brother Reverend A. C. Robinson played harmonica, and

the two made a dynamic team that broadcast a popular West Coast gospel music

show on the radio. L. C. Robinson was

typical of numerous Brazos Valley Blues greats like Pee Wee Creighton, Tomcat

Courtney, Blind Arvella Gray (also from Somerville), Albert Collins and Nat

Dove who found it prudent to leave Texas to find acceptance and success. L. C.

died in Berkeley, California in 1976.

L. C. (Lightnin' Junior") Williams

L. C. (Lightnin' Junior") Williams

L.C. Williams (center) makes a toast

to his blues buddies while in Houston. Sam “Lightnin” Hopkins stands on the

right.

Energetic and

multi-talented, L. C. Williams was

born in 1924, just ten miles north of Navasota in Brazos County in Millican,

Texas. Primarily a singer and drummer,

he was also a gifted dancer. When just 25 years old, he recorded a huge local hit

called “Ethyl Mae” for Freedom records and put the small Houston-based studio

on the blues map. L. C. followed this

hit in 1950 with “Jelly Roll” and “My Darkest Hour,” two more Freedom hits that

sealed his legacy as a recording artist.

L. C. soon became known as “Lightnin’ Junior,” because he often

kept company with Lightnin’ Hopkins. It

was while accompanying L. C. Williams at Gold Star Studio that Hopkins recorded

some of his most respected instrumental work on the guitar and piano,

especially on the song “Trying, Trying,” which may indicate the regard the King

of Texas Blues held for the young Millican native. This may also have been a way to return a

favor in kind, since Williams had backed him and even tap danced on some of his

records.

But fame and financial success came excruciatingly slow. The music buying public became more sophisticated and thus increasingly hard to impress. Record companies would release only the very best of a large stable of recording artists, combining them into one collection, hoping to increase sales, so all of his songs appeared on Blues compilations. Even so, “Lightnin’ Junior” managed to record numerous releases, ultimately gracing the grooves of 17 albums. Sadly, after ten years in the industry, he never saw an album released under his name. It is said that he was consumed by alcoholism, and died of tuberculosis in Houston in 1960. His music was silenced when just 36 years old.

But fame and financial success came excruciatingly slow. The music buying public became more sophisticated and thus increasingly hard to impress. Record companies would release only the very best of a large stable of recording artists, combining them into one collection, hoping to increase sales, so all of his songs appeared on Blues compilations. Even so, “Lightnin’ Junior” managed to record numerous releases, ultimately gracing the grooves of 17 albums. Sadly, after ten years in the industry, he never saw an album released under his name. It is said that he was consumed by alcoholism, and died of tuberculosis in Houston in 1960. His music was silenced when just 36 years old.

He picked up

his music future while in prison, and came out a respectable Dobro player,

ready to spend his days singing for quarters on the streets of the Midwest.

Walter Dixon had probably heard the celebrated innovator of the blues slide

guitar, Blind Willie Johnson who frequented his hometown neighborhood.

Walter Dixon alias Blind Arvella Gray.

By the mid

1940's he was in St Louis, and

Louisville, and later Chicago, trying to sing his songs, perhaps trying to

forget his past, his lifelong injuries, his lost loved ones in Texas, and

playing a zesty slide tribute to his hometown blues masters.

And,

stranger than fiction, it turned out to be a case of a black man indebted to a

little white boy...

An old man

was “discovered” in the 60's busking for dollars at a Chicago flea market and in

time won the fancy of local blues enthusiasts.

The street singer said his name was Arvella Gray. He told all kinds of stories about how he was

blinded. How he lost his fingers. How he came to be in Chicago. A young admirer named Cary Baker connected

him with Birch Records, who cut less than 1000 copies of Blind Arvella’s first

album, entitled The Singing Drifter.

Whoever he was, the old bluesman brought an authentic blues sound to

northern cities that rarely heard such distinct and soulful blues, born in a

different time and place. Blind Arvella Gray enjoyed a reasonable degree of

local celebrity, before passing away, an old man, in 1980.

Having been

blinded, and served time in prison, Walter Dixon, aka Blind Arvella Gray would

be the quintessential bluesman, except for one thing. He did not die young. And his music was not forgotten. Over the

years The Singing Drifter became such a collector’s item that Cary Baker, his

youthful discoverer, arranged its re-release in 2004.

TOM CAT COURTNEY

Albert Collins, the gentle blues giant, was born in

Leona, Texas in 1932. A cousin of the legendary Hopkins clan and Texas

Alexander, he grew up with music as more than just a pastime occupation. Blues

were the family bread and butter, and had been for years. When his family left

Leon County in 1941 and moved to Houston, little Albert took a mind full of his

blues heritage and Leon County with him.

As fate would have it he grew up in the same Houston neighborhood with Johnny

“Guitar’ Watson and Johnny Copeland. Like many other young blues lovers, he

loved and emulated the electric guitar style of Texas’ own T-Bone Walker, but

was even more inspired by John Lee Hooker’s Boogie Chilun’.

He played and socialized with the very hottest names in Texas blues; Gatemouth Brown, Johnny Winter, Janis Joplin and B. B. King. Later he warmed up for Canned Heat. Ironically, he was called the “Ice man.” But what made him great were his own contributions to the changing face of modern blues music.

He played and socialized with the very hottest names in Texas blues; Gatemouth Brown, Johnny Winter, Janis Joplin and B. B. King. Later he warmed up for Canned Heat. Ironically, he was called the “Ice man.” But what made him great were his own contributions to the changing face of modern blues music.

Albert

Collins had a love affair with his audiences that generated a devoted

following, all over America, Canada, Europe and Japan. Collins and his

generation of blues artists lived during the era when blues became almost

mainstream, and crossed over easily between racial groups. And it was his passion to reach out and

express himself to people of all classes and colors. Borrowing a stage antic

from Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones, he would stroll and gyrate amongst his thrilled

fans while he played during concerts, one of the first big stars to drag along

enough guitar cord to reach into the heart of his adoring crowd. His powerful

speakers set on treble to the max, his relentless, dynamic finger-picking took

electric blues and its fans to a new height.

He would often leave the stage while playing, as if in a mad trance, and take his guitar down the street. He supposedly ordered a pizza once after leaving a gig, playing the whole time.

He would often leave the stage while playing, as if in a mad trance, and take his guitar down the street. He supposedly ordered a pizza once after leaving a gig, playing the whole time.

Albert

Collins was known by most in his circle to use some peculiar tuning on his

electric guitar. Gatemouth Brown had introduced him to the much maligned capo,

which many purists reject out of hand. But Collins was no purist. He was an

artist. Supposedly his cousin Willow Young had introduced him to his strange

style of tuning his Fender Telecaster guitar.

Sometimes tuned in open F minor or “double G,” it took a specialist to play

a guitar with his peculiar tuning.

Once a

self-proclaimed guitar wonder asked if he could play Albert’s guitar, and

Collins handed his instrument over with respectful courtesy… and restrained

skepticism. “Sure,” he shrugged. He was after all quite secure, and a

gentleman, if not a bit of a prankster. The neophyte grabbed the guitar as if

it were a loaded grenade launcher, beaming with euphoria, as his big chance had

finally arrived. Assuming standard tuning, he began to show his stuff. But the

more he stroked, the worse he sounded. Everyone had a good laugh, knowing

exactly what was going down. In the end, the poor fellow had to walk away, stunned

and defeated, for he could not seem to play at all. No doubt an immediate case

of blues enveloped him, before he realized that nobody except Albert Collins

could play that guitar.

Albert’s

wife Gwendolyn wrote a lot of his music, and helped manage his business. They

were married a long stretch for an entertainment family, making it to their

Silver Anniversary. Only death parted

them. This in itself may have been blues history. Few enduring couples have

emerged in the Texas blues scene.

Like So many

Texas blues artists, Albert Collins spent the most prosperous years of his life

in California, where he found a reliable and growing market for blues. Quite

ill in his later years, blues songwriter Doug MacLeod went to visit him, one

last time. Collins was dying of lung cancer but was quick to recognize Macleod

and greeted him with a question that would turn attention to his visitor, as if

he had all the time in the world. “Dubb,

have you written me another song?” he asked, knowing well he would never record

again.

“How many do

you want?” quipped MacLeod. Besides money, nothing inspires artists more than

other artists. Collins had drawn from a rich well of Texas blues, and he poured

himself out with equal passion.

Blues is a

devoted family of music, bound by love, loyalty and usually, generous amounts

of liquor. Albert Collins was also rare

because he did not drink in the last ten years of his life. Still, even with all his clean living, he

died at 61. Even in death he broke

another family tradition, and was buried in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Juke Boy Bonner of Bellville

Juke Boy Bonner’s lyrics are thought of by some critics as

something akin to poetry. He was a hard driving boogie blues musician with a

gift for word crafting and social commentary, who unfortunately lived and drank

as hard as he performed. Blues fit his

life and temperament, and although his music set him apart, he struggled all of

his life, and especially with his record labels. He did songs for Goldband, Storyville and Jan

& Dill, until Arhoolie picked him up in 1967. A hospital stay because of stomach problems

led to an intensification of his poetry writing, which ultimately ended up on

vinyl, cutting what is considered his best work for Arhoolie in the late 60's.

The same Blues revival that gave Mance Lipscomb his late-blooming fame took

Juke Boy on a European tour and numerous gigs around the country, but the

revival was too short and the reward fleeting.

Later he recorded for Sonet and Home Cooking.

He never had a big hit, but his music has withstood the test of

time. Many consider him to be an underrated Blues master who never got his big

break, and died before it could happen. Ironically, most agree that it was his

tragic life that made his music so poignant, a paradox that describes many

blues musicians. Juke Boy Bonner ended

up working as a chicken processor before dying of cirrhosis of the liver just

ten days after Juneteenth, 1978.

Joe Tex, aka Joseph Hazziez

Joe was born in 1935, and he did not stay in

Rogers long. He moved to Baytown first, but longed for the country. Family ties brought him to Grimes County where he rests today. Old time Navasota residents remember his easy personality,

contagious sense of humor and down to earth accessibility. They sketch mostly

warm memories of him at local barbecues, hauling watermelons and making small

talk downtown.

Joe was

singing early, winning talent contests as he drew upon his country and blues

heritage, crafting a unique 60's Rock & Roll/ Soul/ R&B style that

sounded like preaching to music. He had several big hits, and made music

history in several ways. The most

important contribution he made to American music was his fearless shifting

between talking and laughing and singing as natural as if he could entertain

during conversation or converse while entertaining. Joe Tex also sang boldly about male - female

relationships, and often included sound advice to his audience, as if he were

doing mass musical marriage counseling. Everyone remembers his strange and

somehow endearing sermon/song “Skinny Legs and All” that blasted, “Who’ll take

the woman with the skinny legs?” But Joe

was full of surprises, recording a country album, which actually brought

considerable acclaim. His biggest hit, “I Gotcha,” was recorded in 1971.

After

spending some time in Baytown, Joe bought a ranch in Grimes County, where he

tried to return to his rural roots and learn more about God. He became a Muslim. After a short sabbatical, he emerged

energized and inspired, cranking out his smash disco hit, Ain’t Gonna Bump No

More (With No Big Fat Woman). Joe had a

way of surprising all of us, even his Muslim brethren. His

talent went from R&B to Rock to Country to Disco. Writing and recording

several hits during his heyday, Joe Tex built his style around just being

himself and having fun while sharing his country charm and wisdom. And many music historians point to his style

as the launching pad for Rap music. For

sure, he is one of the most underestimated R&B entertainers of the 60's and

70's. John Morthland of Texas Monthly

Magazine generously offered that Joe Tex was "by far Texas' greatest

contributor to soul music."

Perhaps, but

Joe was such a whirlwind that he kept his audiences just like his music,

constantly off center, never leaving time for reflection until he was

gone. Joe Tex died of heart failure in

1981. No other Texas entertainer has

covered as much ground, or done it with as much originality or prowess.

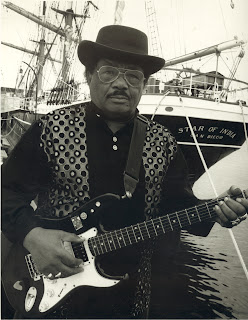

Nat Dove

A great career in entertainment was begun many years ago by a stellar music instructor, Dr. Waymon T. Webster PhD, who taught his high school students excellence and persistence. And little could he have known that one of the young aspiring musicians out there marching in his band would someday be a popular blues musician and recording artist. And in turn, Nat Dove would teach the same values to his own fans and students, who stretch all over the globe. It all started in and around Bryan, Texas, but the ripple made by that instructor has made it to Paris, Los Angeles, and Tokyo.

There are just a handful of what we could call old time, first generation Texas blues men left in this country. They are passing from the scene too fast. And Nat Dove is not only one of them, he is from our area, and deserves great attention and veneration.

Nat is not your garden variety old blues guy, sitting on an urban bench strumming an old beat-up guitar for donations. He is not your garden variety anything. His career is the product of a lifetime of passionate, diligent pursuit of excellence. A man with this kind of character and talent could have been anything, but thank goodness Nat chose music, and not just any kind of music, but Texas blues. That makes Nat the very embodiment of everything I have been studying and portraying in my blues museum at Blues Alley. So you will not be surprised when I confide that he has been a great source of information and inspiration. So enough wallowing and waxing in my own syrup…

Nat Dove was born in Mumford, Texas in 1939. Mumford is just a nondescript village a few miles west of Bryan, Texas where he attended High School. Nat grew up literally engulfed in the Texas cotton industry, surrounded by cotton farms as far as the eye could see. The only thing that broke the Brazos bottom monotony was the lethargic dipping of a few pump jacks here and there. Church was the center of his lifestyle, and going to church every Sunday and making music was a part of the family tradition.

Nat hit the piano when just four years old, and never let go. Music became his window out of Mumford, his stairway to the sky, and he played and prospered in this dusty dirt road microcosm. Soon he began to hear a different tune. Something irresistible. Something that made his spirit and his body move. Something that was about to set the whole music world on fire.

Before there was rock n’ roll, there was blues and one of its many offspring, Texas boogie. On Sunday afternoons, when he and his sisters were only allowed to play Gospel music, Nat began to play his new-found melodies. To avoid opposition, he slowed them down and played them Oh so reverently. Suddenly everybody was interested in what was going on around the piano. I’m sure his mother tried to wrap her mind around what she was hearing… I can imagine her shaking her head in the kitchen thinking, “I don’t remember that one!” And Nat would never forget those days, or the nurturing environment he enjoyed in those formative years. No matter what he did, he was taught to give it his all, to be the best. I have no doubt he is the product of a superior upbringing, where excellence was the cornerstone.

Like all young men, Nat jumped some fences so to speak, and began to seek the sources of his new sound. The Brazos bottom was teaming with blues and blues men and blues venues. Juke joints; River bottom dives where the mostly non-churchgoing types hung out. These were smoky, dangerous places where whores skulked around and cotton pickers and mule drivers gambled, drank and occasionally cut each other up. And in the peaceful moments, barrelhouse piano players like Buster Pickens of Hempstead hammered away on the battle-scarred and stained ivories with abandon. These people worked hard and played hard and they liked their music hard. Their music was as edgy as the hoes and shovels and discs and axes they used to work the earth.

But blues had morphed from the wailing wagonloads of moans of the early nineteen-hundreds into a hopped-up eight-cylinder engine lubricated by fermented corn juice. It was a dark, seductive, invigorating world, and musicians were kings.

Nat was soon playing with Brazos Valley music royalty, and making a niche for himself. It was the Fifties, and boogie was taking over the sound in the bottoms, and inspiring another blues child: Rock n’ roll. Black artists like Juke Boy Bonner, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Pee Wee Crayton and T-Bone Walker were making electric guitar and Texas boogie popular. Nat found a niche by playing the piano in this new upbeat style, and found a legacy in the process. Visits to his uncle’s recording studio in Houston clinched his future, where he met Big Mama Thornton and sat in as a drummer and watched other upcoming blues and boogie artists cut records and launch their careers. Rock music was about to change music forever, and there was a race to keep up with the music. There was just one thing to do. Like many other Texas bluesmen, Nat succumbed to the overwhelming magnet of California.

By the sixties, Nat was established in California, with an all–star boogie band. It seems incredible now, truly historic, but at the time Nat was just following his passion. But there he was in Hollywood, playing piano with Pee Wee Crayton’s lead guitar, Mickey Champion’s vocals, and Big Jim Wynn’s sax. Soon Nat was an often requested West Coast studio pianist. That led to tours, contracts and soundtracks, and a resume that reads like the Who’s Who of West Coast blues. Nat has played and recorded with Big Mama Thornton, Little Johnny Taylor, Sam Cooke, Robert Cray and Lowell Fulson, just to name names, and many others.

By the seventies, Nat was travelling the world, doing concerts in Europe and Japan and sharing his love for Texas boogie with audiences far removed from those dirt roads in Mumford. So well was he received in Paris that he just adopted the place and stayed for a decade, becoming the Composer in Residence at the American Culture Center in Paris. If rejection is hell, then acceptance is an earthly taste of heaven and Nat has certainly had his taste of that. Sadly, he has found more of it in far-away places than his own native backyard.

Perhaps Dove’s most memorable contribution to his craft was writing the original score for Rudy Ray Moore’s classic film in the 1970’s, “Petey Wheatstraw.”

The rest is a long history you can read about on his website, natdove.com. If you go to the Press & Reviews page, it is led off with my glowing account of one of his appearances here in Navasota. I meant every word. I am very proud to know him and help put a shine his inspiring story. Nat Dove was recently inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, with a life time achievement award.

But since 2003, Nat has been back home in the States now, having settled in Oakland California, and spends his time nurturing what his parents instilled in him; education, writing, performing and teaching young people an appreciation for music and excellence. He was inducted into the West Coast Blues Hall of Fame in 2008. He has started to recieve the attention he has earned after a long process of living his commitment to give back as much, or more, in life than he received. After all is said and done, Nat Dove learned his Sunday School lessons well.

A great career in entertainment was begun many years ago by a stellar music instructor, Dr. Waymon T. Webster PhD, who taught his high school students excellence and persistence. And little could he have known that one of the young aspiring musicians out there marching in his band would someday be a popular blues musician and recording artist. And in turn, Nat Dove would teach the same values to his own fans and students, who stretch all over the globe. It all started in and around Bryan, Texas, but the ripple made by that instructor has made it to Paris, Los Angeles, and Tokyo.

There are just a handful of what we could call old time, first generation Texas blues men left in this country. They are passing from the scene too fast. And Nat Dove is not only one of them, he is from our area, and deserves great attention and veneration.

Nat is not your garden variety old blues guy, sitting on an urban bench strumming an old beat-up guitar for donations. He is not your garden variety anything. His career is the product of a lifetime of passionate, diligent pursuit of excellence. A man with this kind of character and talent could have been anything, but thank goodness Nat chose music, and not just any kind of music, but Texas blues. That makes Nat the very embodiment of everything I have been studying and portraying in my blues museum at Blues Alley. So you will not be surprised when I confide that he has been a great source of information and inspiration. So enough wallowing and waxing in my own syrup…

Nat Dove was born in Mumford, Texas in 1939. Mumford is just a nondescript village a few miles west of Bryan, Texas where he attended High School. Nat grew up literally engulfed in the Texas cotton industry, surrounded by cotton farms as far as the eye could see. The only thing that broke the Brazos bottom monotony was the lethargic dipping of a few pump jacks here and there. Church was the center of his lifestyle, and going to church every Sunday and making music was a part of the family tradition.

Nat hit the piano when just four years old, and never let go. Music became his window out of Mumford, his stairway to the sky, and he played and prospered in this dusty dirt road microcosm. Soon he began to hear a different tune. Something irresistible. Something that made his spirit and his body move. Something that was about to set the whole music world on fire.

Before there was rock n’ roll, there was blues and one of its many offspring, Texas boogie. On Sunday afternoons, when he and his sisters were only allowed to play Gospel music, Nat began to play his new-found melodies. To avoid opposition, he slowed them down and played them Oh so reverently. Suddenly everybody was interested in what was going on around the piano. I’m sure his mother tried to wrap her mind around what she was hearing… I can imagine her shaking her head in the kitchen thinking, “I don’t remember that one!” And Nat would never forget those days, or the nurturing environment he enjoyed in those formative years. No matter what he did, he was taught to give it his all, to be the best. I have no doubt he is the product of a superior upbringing, where excellence was the cornerstone.

Like all young men, Nat jumped some fences so to speak, and began to seek the sources of his new sound. The Brazos bottom was teaming with blues and blues men and blues venues. Juke joints; River bottom dives where the mostly non-churchgoing types hung out. These were smoky, dangerous places where whores skulked around and cotton pickers and mule drivers gambled, drank and occasionally cut each other up. And in the peaceful moments, barrelhouse piano players like Buster Pickens of Hempstead hammered away on the battle-scarred and stained ivories with abandon. These people worked hard and played hard and they liked their music hard. Their music was as edgy as the hoes and shovels and discs and axes they used to work the earth.

But blues had morphed from the wailing wagonloads of moans of the early nineteen-hundreds into a hopped-up eight-cylinder engine lubricated by fermented corn juice. It was a dark, seductive, invigorating world, and musicians were kings.

Nat was soon playing with Brazos Valley music royalty, and making a niche for himself. It was the Fifties, and boogie was taking over the sound in the bottoms, and inspiring another blues child: Rock n’ roll. Black artists like Juke Boy Bonner, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Pee Wee Crayton and T-Bone Walker were making electric guitar and Texas boogie popular. Nat found a niche by playing the piano in this new upbeat style, and found a legacy in the process. Visits to his uncle’s recording studio in Houston clinched his future, where he met Big Mama Thornton and sat in as a drummer and watched other upcoming blues and boogie artists cut records and launch their careers. Rock music was about to change music forever, and there was a race to keep up with the music. There was just one thing to do. Like many other Texas bluesmen, Nat succumbed to the overwhelming magnet of California.

By the sixties, Nat was established in California, with an all–star boogie band. It seems incredible now, truly historic, but at the time Nat was just following his passion. But there he was in Hollywood, playing piano with Pee Wee Crayton’s lead guitar, Mickey Champion’s vocals, and Big Jim Wynn’s sax. Soon Nat was an often requested West Coast studio pianist. That led to tours, contracts and soundtracks, and a resume that reads like the Who’s Who of West Coast blues. Nat has played and recorded with Big Mama Thornton, Little Johnny Taylor, Sam Cooke, Robert Cray and Lowell Fulson, just to name names, and many others.

By the seventies, Nat was travelling the world, doing concerts in Europe and Japan and sharing his love for Texas boogie with audiences far removed from those dirt roads in Mumford. So well was he received in Paris that he just adopted the place and stayed for a decade, becoming the Composer in Residence at the American Culture Center in Paris. If rejection is hell, then acceptance is an earthly taste of heaven and Nat has certainly had his taste of that. Sadly, he has found more of it in far-away places than his own native backyard.

Perhaps Dove’s most memorable contribution to his craft was writing the original score for Rudy Ray Moore’s classic film in the 1970’s, “Petey Wheatstraw.”

The rest is a long history you can read about on his website, natdove.com. If you go to the Press & Reviews page, it is led off with my glowing account of one of his appearances here in Navasota. I meant every word. I am very proud to know him and help put a shine his inspiring story. Nat Dove was recently inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, with a life time achievement award.

But since 2003, Nat has been back home in the States now, having settled in Oakland California, and spends his time nurturing what his parents instilled in him; education, writing, performing and teaching young people an appreciation for music and excellence. He was inducted into the West Coast Blues Hall of Fame in 2008. He has started to recieve the attention he has earned after a long process of living his commitment to give back as much, or more, in life than he received. After all is said and done, Nat Dove learned his Sunday School lessons well.

Nat recently returned to France and was able to introduce his wife to many old fans and friends who know him there as the “Texas Boogie King.” This is just one of his titles. Professor of Blues Music is another one.

Nat Dove takes as much pride in being an educator as he does being a successful entertainer. Since returning from Asia, Nat is a sought after university lecturer. He is also featured in a recently released documentary film entitled: “Slave Routes” which was filmed at New York University in 2008.

Over the

years Nat has come to realize the importance of giving back to the society that

gave him a chance to reach for and attain his dream. He travels all over the

United States doing workshops for young people, or any people interested in

music, especially blues music.

Sadly,

Nat finds less young people in his culture today interested in performing music

than during his youth. He remembers a

good sized band marching for his Alma mater, E. A. Kemp High School, and an

active music tradition while growing up in Bryan. There was gospel, blues, and other popular

music as well. The Brazos Valley was the epicenter of Texas blues, with

talented blues performers as common as preachers or politicians. Nat recalls

hearing many legendary blues greats playing right here in the Brazos Valley.

There was Lightnin’ Hopkins of Centerville, Mance Lipscomb of Navasota, Pee Wee

Crayton of Rockdale, Juke Boy Bonner from Bellville, Slim Green of Bryan,

Tomcat Courtney of Waco and Buster Pickens from Hempstead. These performers were only just a few of

scores who were following a path already blazed by local blues legends Blind

Willie Johnson of Temple and Texas Alexander of Richards. Brazos Bottom juke-

joints at Mumford, Allenfarm and Clay Station kept blues cranking during these

formative years.

This region

was a veritable spawning pond of blues and blues masters. So one might find it

strange how Dove, like most of his predecessors would find more support and

acceptance for his craft in Europe than in his home state. But after all of

these years, he still wants to change that. No matter the thrill of applause

from French or Japanese fans, there is still something about pleasing home town

folks. And more important to Dove is inspiring the next generation of artists

to rise from their north side environment and to achieve their artistic dreams.

Nat Dove comes

back to his roots often, playing for various groups in Brazos County,

conducting music workshops and clinics and performing at the annual Navasota

Bluesfest as often as he can. And he is

starting to write down his observations like never before. Moved by the subtle trends and unseen forces

that spread the blues from coast to coast,

Dove has decided to write a series of essays to form a book explaining

his unique perspective on the history of blues music. If he has his way, his

recollections will serve to energize the next musical wave to be born in this

Brazos Valley blues incubator. The rich fertile soil of the cotton bottoms was

once the birthplace for a music genre that reached all over the world, even

carried by NASA into outer space. Now Nat Dove just wants to bring it back

home.

It was

through several conversations with Nat that I got the impression that somebody

needed to lay out the incredible story woven into this book, as he convinced me

the story I was sniffing out was there, and even more significant than I could

know. In fact Nat believes and teaches everywhere he goes, that blues music is

America’s classical music, and should be appreciated as such.

One would

like to think his former high school teacher, Dr. Waymon T. Webster of Prairie

View A&M University would be very proud.

Three more inspiring achievers in the

entertainment industry, strongly related to the blues, who passed through Blues

Valley, should be included in this collection of Blues Valley greats. One was an

Opera singer, another a dancer, and the other a cook, and the last two did for

dance and barbecue what W. C. Handy did for blues…

Alvin Ailey

Alvin Ailey was born in Rogers, Texas in

1931. Lula, his mother remembered, “

…he got busy as soon as he was born.”

Determined to carry him everywhere since he showed reluctance to walk,

after 18 months his unusual size made her finally set him down, to walk on his

own. In a telltale instant, he spun like a top and did a couple of little

flips. Lula was stunned at his

athleticism, but he shrugged off her surprise, and claimed his feet had just never

been allowed to touch the ground. Those feet were to cover many miles with her,

and ultimately dance all over the world.

Alvin came with his mother to Navasota in 1936 at age 5 where she had answered an advertisement looking for cooks to prepare food for Texas highway workers. She often worked in the cotton patch, and he grew up in the fields, picking flowers, prancing from furrow to furrow, and attending school in Navasota where he showed an interest in art. He later recalled these to be the happiest days of his life.

Alvin came with his mother to Navasota in 1936 at age 5 where she had answered an advertisement looking for cooks to prepare food for Texas highway workers. She often worked in the cotton patch, and he grew up in the fields, picking flowers, prancing from furrow to furrow, and attending school in Navasota where he showed an interest in art. He later recalled these to be the happiest days of his life.

For Ailey,

the struggle was not the plantation system or Southern racial oppression, for

he had been saved from that when young, but finding acceptance as an artist in

a field that did not yet exist.

Life in

rural Texas was very hard for black farm workers. Each day was a struggle

against poverty, racism, unmerciful weather, and depression. Alvin was raised in a family where hope was

kept alive by the Faith learned at the local church. That hope led them to

better job opportunities in California in 1942, where he discovered his

lifelong passion: Dance. As a teen in

Los Angeles, he studied under Lester Horton, and began to emerge with a style

all his own. By 1954 he was in New York,

ready to make a lasting mark on the world of Dance. In 1958 he and his cronies

were unveiled as “The Alvin Ailey

American Dance Theatre,” at the

92nd Street Young Men’s Hebrew Association. In the 60’s he led what he called “station

wagon tours” all over the northeast.

They were

widely acclaimed as they performed his show called “Blues Suite,” which

mastered in dance what Alvin had grown up seeing and hearing in the cotton

fields, a bodily interpretation of blues. And that was just the beginning.

Today he is

remembered as a daring iconoclast, a breathtaking dancer, an innovative

choreographer and an entertainment visionary.

He died in 1989 of blood dyscrasia, leaving a legend in mid birth. But the name Alvin Ailey will far outlive his

struggles and talents that took him to the top.

Every year, on New Year’s Eve, it is at his dance theater that the high

society of New York meets to welcome in the New Year. His

very name has become synonymous with personal achievement, hope and new

beginnings. The contribution he made to American dance and entertainment as

a whole may never be quantified.

His first

restaurant was in Lubbock, started after his return from the Korean War, where

he was wounded twice. He looked for

something to do besides pick cotton, something he had done ever since he

was a little boy in the Brazos River bottom near Navasota, where he was

born in 1931. Two things emerged in his new

enterprise, both remnants from his childhood; Barbecue and Blues. As his barbecue filled bellies, singers like

Muddy Waters, or Johnny Cash or Emmy Lou Harris filled the ears of his

customers. Some musicians would play for

tips, just to say they had played there. Nobody seemed to mind when he would take the

mic and sin g one himself. But he never

quit his day job. “I want to feed the world” he would say with a big Texas smile. It was a sad day in Lubbock when his historic

place burned down.

“Stubb” used

the change for the better, and moved his two loves to Austin, and used the same

ingredients to satisfy the apatite of a whole new generation. Stubb’s was THE

place for fresh barbecue and music. He

passed away in 1995. Like all restaurateurs,

he had his struggles, but his legacy of Texas entertainment still lives

on. Every time you see his face on a

bottle of sauce, remember he started his remarkable life in Navasota, and he

loved people and listening to the blues and feeding people. A man could do a

whole lot worse.

You already read about the blues artists from the rich heart of Blues Valley, from Millican, Navasota, Brenham, Somerville, Hempstead, and Bellville.

Unexplainably for a city its size, there were few known blues recording artists besides Tomcat Courtney from around Waco. Blind Willie Johnson lived and preached around Temple and Marlin, and he is the only internationally known blues artist from the north end of the Brazos. In Bryan there was Norman G. "Guitar Slim” Green born in 1907, and Nat Dove, who is still going strong, and like Tomcat Courtney, now living in California.

After the

rivers joined at Navasota there were hot blues players all the way to the Gulf of

Mexico. Walter Booker of Prairie View,

in Waller County, Huey and Jewell

Long of San Felipe, and Jerome

Richardson of Sealy in Austin County, Harold Holiday, aka “Black Boy Shine” of Richmond, in Ft

Bend County, Leadbelly and a host of

other inmates in Brazoria, and Robert

“Fud” Shaw of Stafford, in Brazoria County.

Houston was

teaming with country boys who claimed the Bayou City as their home, and many

biographies were never written to identify their birth places, but all of them

sang about Blues Valley like it was their ancestral home. We must stare in

wonder at this valley, and wonder at the talent that was spawned, relatively

ignored, which found devoted audiences around the world, and wonder at our own

lack of intellect and artistic appreciation. Regardless, the music survived and

sang its own story, and now even in Blues Valley, it might see the light of day.

In

progress: An artist rendered map of Blues Valley, which encompasses 18 counties

along the Brazos and Navasota Rivers and their tributaries, showing the

landmarks and hometowns of blues artists.

No comments:

Post a Comment